Denmark recently raises retirement age to 70 – Retirement Research Centre

We should also restore the balance of the system, but inequality precludes an overall increase.

Denmark recently raised the retirement age for Danes born in 1971 or later. Should we do the same? The answer is two aspects.

On the one hand, Congress should enact legislation to restore balance to our social security system, and the costs faced in 10 years are also increasing like Denmark. Our benefits currently exceed our income and the funds in this trust fund cover insufficient funds. In 2033, reserves in trust funds will be exhausted and retirement benefits will be reduced by 23% to match incoming income. To avoid such a huge and sudden welfare, Congress must develop a package to eliminate the shortcomings of the plan. Congress should act as soon as possible, rather than later, to relieve anxiety among many older Americans and to distribute burdens in fair ways across different cohorts.

On the other hand, unlike Denmark, the United States has not been able to grow at the retirement age as our society is more inequality than Denmark. According to the OECD, the poverty rate in the United States is almost three times that in Denmark, and a more comprehensive measure of inequality (Gini coefficient) shows the overall distribution of inequality in household income (see Figure 1). (The GINI coefficient of zero indicates that income is distributed evenly across all households, and a value of 1 indicates that one household receives all income.)

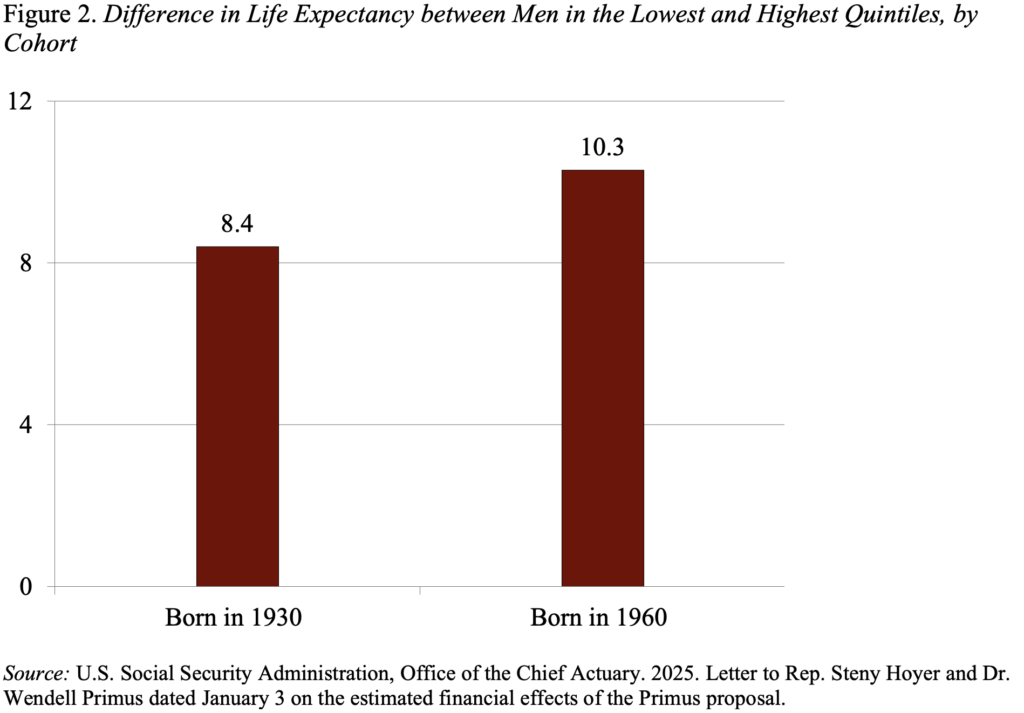

Income inequality directly translates into life expectancy inequality. Remember that the argument for higher retirement age is based on the premise that people live longer, so why not work longer. Yes, on average, we have gained in life expectancy, but these gains have mostly enjoyed the first half of the year.

The latest research by Social Security Actuaries supports a wide range of evidence, which brings this to the House of Spades. As a record, actuary’s figures may underestimate the relationship between benefits and life expectancy for two reasons. First, these calculations exclude all workers who receive benefits under the disability insurance plan, a low-income group with low-income life expectancy that they will lower their estimates by a minimum of one-fifth. Second, unlike early studies, these figures are related to life expectancy at 62 years. Eliminating those who die between the ages of 50 and 62 will generally create healthier groups. Despite these biases, their analysis of all workers claiming retirement benefits shows that life expectancy increases with increasing income and gaps (see Table 1).

The results show that although life expectancy increased from 18.1 year for men born in 1930 to 1960, the top 20% increased by more than twice as many as for men in the lowest 20% of men, and the difference between the two groups increased, so men now can expect to be 10 years longer than men at the bottom (see Figure 2). That is to say, the bottom-level men in the profit distribution are expected to live about 77 years, while the top-level men are expected to live in 88.

Due to the huge difference in life expectancy, commentators have proposed adding the full retirement age only to those who can work longer. That is, only the top 20% of each cohort can work before 70 and will increase to keep low-income people at their current retirement age of 67.

Most importantly, Denmark’s growth in retirement age has strengthened the fact that we need to restore balance and confidence in our social security programs. But the United States cannot adopt the same choice as Denmark, because life expectancy and life expectancy growth vary by income, and our income distribution is very unequal.

Source link